These are some shots taken on a very cold Ballycotton Pier this morning with the extraordinary little pocket marvel, the Sony RX100.

All were shot in RAW and processed in Adobe Camera Raw and Photoshop CS6. ISO 400.

I was asked to photograph the Cork vocal ensemble Madrigal 75 during their lunchtime recital at St Colman’s Cathedral, Cobh on March 23rd.

If there is one thing I’ve learned from photographing the East Cork Early Music Festival during the last couple of years is that the lighting at venues is rarely ideal from a photographic perspective. Low lighting appears to be the norm probably, in the case of some of the ECEMF concerts at least, because of the effect that harsh, bright light might have on the tuning of the period instruments.

And even though there were no instruments involved in the Madrigal 75 recital – just their pristine, glorious voices – the lighting on the singers, as expected, was muted. The use of flash, of course, was out of the question as it would have been distracting both to the performers and the audience. Another consideration is to be careful when releasing the shutter – one has to make the exposures during the louder versions of the performances: there is nothing worse than hearing “click, click, click” during a quiet passage.

You also have to blend in. Dark clothing is pretty well de rigeur – walking around (and you mustn’t do much of that either) wearing a loud shirt and bright jeans would only serve as another distraction. One has to be respectful of the performers and the audience at all times.

I arrived about an hour before the recital and, luckily, they were rehearsing. This afforded me the opportunity of checking the optimum camera settings as well as the best vantage points.

The altar in front of which they were singing was brightly lit whereas the light on themselves was, as I say, muted.

This is an unprocessed RAW shot showing the relative brightness levels:

The exposure chosen results in a brighter scene than it was in reality.

In order to expose them properly I needed to use an ISO of 6400 and shutter speeds of between 1/160 sec and 1/60 sec depending on whether I was using the Sigma 70-200 f/2.8 or the Canon 400mm f/5.6. 1/60 sec is a bit slow when using a 400mm lens but I had no choice. Naturally I shot in RAW in order to (a) not worry about the White Balance and (b) give me plenty of exposure latitude. I used a monopod throughout.

When I processed the shots in Adobe Camera Raw I adjusted the WB to Fluorescent as it gave me the most pleasing results.

ISO of 6400 is a frightening speed to someone like me who cut my photographic teeth with film. Back then ISO 400 was pushing the envelope and it resulted in gloriously grainy shots (remember Tri-X?) Some artistic photographers like Sarah Moon in the 1970s used GAF 500 slide film – then the fastest available – and the results had grain as big as golf balls.

Now we can use ISOs of 6400 and greater and the “noise” – the digital equivalent of film grain – is so well controlled and almost imperceptible as to be nothing short of miraculous. There are even methods of reducing noise in post-processing such as the native ACR one or third party software like Noise Ninja. Personally, I like a bit of noise when using high ISOs. You can easily reduce noise to such an extent that the skin of the subjects begins to look “plasticky”.

Here is a 100% crop of one of the performers before (on the left) any noise reduction and (on the right) with the Luminance slider in ACR set to 35:

You can reduce it still further of course but you are risking the plastic look. Don’t be afraid of grain/noise – not all images have to be crispy clean.

This is the colour straight from the camera:

And this is with the White Balance set to Fluorescent and other adjustments (Clarity, Vibrance, Saturation) made in ACR and then cropped in Photoshop:

It was a pleasure to photograph such a wonderful group.

The photos can be seen on Madrigal 75’s Facebook page:

https://www.facebook.com/Madrigal75?fref=ts

For more information check out:

Into My Heart An Air That Kills

From Yon Far Country Blows

What Are Those Blue Remembered Hills

What Spires, What Farms Are Those?

Those words by that most melancholic of poets, A. E. Housman, always remind me of my early childhood in the Ireland of the 1950s, where we lived in a little cottage, near Ballymacoda, County Cork, in the townland of Warren, overlooking the sea, and Ballycotton Island.

The view from the back of the cottage – Ballycotton Island is in the distance

(Click on the photos to see them in larger size)

It’s been more than 50 years since we lived there and yet the fields and houses, the boreens and pathways, the streams and seashore have that special resonance for me that the landscapes of all our childhoods invariably have. Their imprint remains for the rest of our lives.

And so, whenever I drive the coast road from Mullins’ Cross to Knockadoon and back via Ballymacoda the past intrudes into the present around nearly every corner.

A few miles from Mullins’ Cross I pass Motherways’ house where my mother worked in the 30s and 40s. The Motherways were farmers and my mother worked as a domestic, doing household chores and looking after the young Motherway children. One of her abiding memories of her time there is of being told of the outbreak of war in September 1939.

A few miles further on I come to where our cottage once stood. It has long since been transformed into a modern bungalow but I can still see my grandfather Jamesy Pomphrett standing by the half-door and the rooms and their furnishings are still clear to me now: the slate tiles on the floor; the dresser with the good ware; the settle; the fireplace and the fire machine; the outside water pump with the large iron handle.

The cottage photographed circa 1974. Jamesy Pomphrett lived there until his death in 1976.

The cottage as it is now (picture from Google Earth).

In the foreground is The Acre which I remember my grandfather ploughing with a couple of horses.

My maternal grandfather Jamesy Pomphrett circa 1974. He died in 1976 at the age of 88. My mother, Nora, is still alive and very well at 97 (born on 28 Feb 1916).

Sometimes I park the car nearby and I take a stroll down the boreen towards what was Eamon Walsh’s house, uninhabited for decades and now used for storing feed for livestock.

The boreen to Walsh’s house which was just around the foreground corner to the right

I wander around the derelict house and farm buildings and I remember how I used to play here with the Walsh’s children.

There is no shouting and laughter to be heard here now, only the sound of the wind whistling around the walls and windows. I feel like a ghost as I explore what remains of the rooms.

Eamon Walsh’s house

From Walsh’s I walk across the fields towards the cliffs and I look across at Ballycotton and the island. In my mind’s eye, the “Innisfallen” hoves into view from behind the island making its way from Cork to Fishguard. The boat used to hug the coastline back then. On board is my father returning to England, to Fords of Dagenham, after a short holiday at home. We used to light a bonfire in this very place to signal our presence to him as the boat passed. In those days our emigrants went by sea.

The “M.V. Inisfallen”. It carried thousands of emigrants to England and many (most?) of them never returned. My father did, in 1961, and we – my parents and sisters and I (my grandfather stayed in the cottage) – moved to Youghal. My parents had contemplated moving the family to London.

I make my way down the cliffs to the strand, a place called The Cow. This is where I used to go with my mother as she picked perriwinkles and carrigeen moss to earn some money in those lean and austere years of the fifties. I would sit in the sun by the side of The Lios (a Fairy Fort) or explore the rockpools as she worked.

“The Cow” – from the Irish “An Cabha” (cove).

The wall, built in the 1940s, has successfully weathered the storms over the years with only minor portions breaking away.

At the Garryvoe end of The Cow, “The Tadorna”, a ship bound from from Rotterdam to Cork, ran aground in November 1911 with no loss of life and was deemed unsalvageable. Its general cargo found its way into houses in the locality.

Another photo of the Tadorna courtesy of Mr Toddy Lawton

All that’s left of “The Tadorna” today.

The mound on which the timber house stands is known as “The Lios” – an Irish word for Fairy Fort. In 2004 local artist and writer Jools Gilson-Ellis staged an installation titled “The Lios” at the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork and at the Phoenix centre in Exeter . Part of the installation consisted of recordings of local people, including my mother, reminiscing about the Lios and the area.

From the shore I walk up the path towards Lawton’s old farmhouse. At the top of the path, on the left, is part of a field where a couple of houses used to be. I vaguely remember them. Helen McCarthy, a childhood friend of my mother’s, was reared in one of those houses. She was a feisty and fun girl according to my mother who remembers her with great affection. She later went to America but returned and married Jimmy Mullins of the aforementioned Mullins’ Cross near Garryvoe. It is sad to think that people loved, lived and played in this very spot and nothing, not a brick nor a stone, remains to stand testament to it.

And as I near what was once Lawton’s house I imagine Tom and Molly coming out to greet me, Molly, as ever, with a cigarette dangling on her lip. There is where the dairy stood, where the cows used to be milked by hand and where the farmyard cats used to get a squirt of milk in the eyes if they greedily ventured too close to one of the milkers.

This is where I made Farmer’s Butter in a wooden tub under the expert eye of Molly. I can still feel the ache in my hand from turning the handle – easy at first and then more difficult as the cream thickened.

My sisters and myself were regular visitors at Lawtons. In those days before television, card playing was a regular occurrence in the evenings. And I remember once how my older sister and myself made our way home across the fields. It was a beautiful night in late summer, I took off my shoes and walked barefoot in the dewy grass, and as I looked up a full harvest moon was rising over the field above Eamon Walsh’s.

Lawton’s house was the second one on the right

One dark winter night my mother took me along a path through some fields until we came to an old iron gate. As I climbed up she told me to look to the northern sky and there we saw the dancing, glimmering lights of the Aurora Borealis. I often wondered if I’d imagined this until a friend of mine confirmed that in 1958 the Northern Lights were observed this far south.

Further up the road is Smiddy’s farmhouse, again, now, empty. Here in the haggard I remember the noise, the smell and the chaff, and the general hustle and bustle, as a threshing machine separated the grain from the stalks and husks of corn one harvest evening.

A typical threshing scene in Ireland in the 1950s. This one was in Inchigeelagh, County Cork. Photo by Aubrey Higgs (via Textlad)

Across the road is the boreen down which we travelled in a horse and trap to Ballymacoda for Sunday Mass.

Further on again is Kilmacdonagh School, now another storage space for a farmer. This is where I first went to school – by bicycle – and learned my lessons from an old, severe woman called the Col Aherne.

Kilmacdonagh National School photographed on film circa 2000

This used to be the playground of the school.

An extract from the school’s roll book of 27/11/1958 showing my entry under the Irish version of my name – “Seán A. Ó Finn”

Update 26th May, 2015: I returned to the school yesterday and with the kind permission of the owner I took the following photographs:

It’s all so long ago, and I think about time, and finitude, and the passing of time, and of the people who lived around us – Tom and Molly Lawton, Eamon and Chrissie Walsh, Dave Carty, John and May Smiddy, the Colberts – all of whom are now hidden amongst the stars – and the way of life that has disappeared, and the changes that time has wrought.

“Time”, said Marcus Aurelius,” is a river, and strong is its current; no sooner is a thing brought to sight than it is swept by and another takes its place, and this too will be swept away.”

As a small child I was too involved in experiencing the world to have such melancholic thoughts but, of course, I too was a prisoner of time. Dylan Thomas, ìn “Fern Hill”, expressed it well:

Oh as I was young and easy in the mercy of his means

Time held me green and dying

Though I sang in my chains like the sea.

Despite dreadful weather conditions this morning – torrential rain and high winds – volunteers were out in force around the country to collect for the Irish Cancer Society’s annual Daffodil Day.

Here’s a selection of photos showing some of the East Cork collectors and members of the supporting public on the street, in supermarkets and shopping malls; holding a very successful coffee morning in Castlemartyr National School; and Transition Year students from Midleton and Carrigtwohill helping this very worthy fund-raising event.

Once again the public have been more than generous in their support. It is a cause that never fails to elicit a great response as cancer, unfortunately, is something that has touched practically every family.

The Irish Cancer Society does tremendous work in providing awareness, care and in supporting research; their mission is to ensure fewer people get cancer and those that do get better outcomes. The annual Daffodil Day collection is hugely important in that respect and has been recognised as such by the public.

Midleton

Jonathan Finn

Anna Hegarty, Claire Hickey, Sarah Daly, Jess Linehan, Amy McKenzie

Stephanie Hartnett, Caoilinn Hickey

Adam Stenhouse

Pauline Clarke

Castlemartyr National School Coffee Morning

Transition Year students from St Aloysius’ College, Carrigtwohill

Orla O’Brien, Andrea McGrath, Mary Twomey and Aisling Cahalane

Here’s a quick and easy way to make a watermark in Photoshop:

1. Open a new document (File/New):

2. Write what you want to appear on your photos:

(The © symbol is obtained by pressing Alt and 0169 on the numeric keypad)

3. Convert that into a brush using Edit/Define Brush Preset:

4. Click on the Brush Tool, arrow down to the last of the brush options and the watermark brush will be there:

All you need is a single click of the brush on the photo and the watermark will be there. The advantages of using a brush to insert a watermark is that you can vary the size, the colour, the location and the opacity to suit an individual photo.

Here is an example of it in use:

1. An unwatermarked photo:

2. By sizing the brush using the square brackets on your keypad (left to decrease, right to increase) you can, if you wish, plaster your watermark across the centre of the photo.

I think that looks horrible!

3. Or you may opt for a more discreet one:

I’m not a fan of watermarks and I rarely use them when posting photos to Flickr, Facebook, etc.

I can understand the need to watermark your online images if you are a wedding photographer or if you monetise your work in some other way. I’m not and I don’t.

But what about people stealing my unprotected images?

Frankly, I’m not that bothered if they do – provided that they do not use them for commercial purposes.

If people want to use an image of mine to illustrate a blogpost or whatever then they are welcome.

It would be nice to be asked beforehand and nicer again to get a credit on whichever site the photo ends up in. I’ve had several such requests and apart from one instance where I did not wish to be associated with the site in question I’ve always given permission.

This is the internet and if you choose to post photos then the chances are that some of them will be used without your knowledge.

A discreet watermark can easily be removed. A large one – as in 2 above – is more difficult to erase but it destroys whatever impact the image may have.

If you are so paranoid about image protection that you are going to do that to your photos then I would seriously question why you bother posting them in the first place.

I received an interesting message via my website – http://www.johnfinnphotography.com – last week:

“My name is Marian Jno-Finn (pronounced John-Finn). I am from Dominica

in the Caribbean. I am very curious as to how that name finds it way to

my village Castle Bruce, Dominica. I am told that my great, great, great

grandfather originated from Ireland . His name was John Finn and made

a child with a slave girl. The Jno-Finn name is only found in my village

because that child relocated to my village and made children.”

Marian Jno-Finn

Dominica is one of the Lesser Antilles – it is pronounced “Domineeka”

My first reaction was that John Finn was one of the 50,000 Irish people who were deported as slaves to the West Indies during the brutal Cromwellian military campaign in Ireland (1649-1653). The consequences of that campaign were every bit as cataclysmic as the Great Famine in the 19th century. Estimates of the number of people who died as a result of warfare and its attendant evils of famine and disease vary from a third to five sixths of the pre-war population. William Petty, an economist with the Cromwellian administration, calculated that 618,000 people died – 40% of the population.

Oliver Cromwell

Whatever the figure there is no dispute about the 50,000 who were sent into slavery. They were deported as “indentured labourers” – slaves – to the colonies in the Caribbean. Many were sent to the island of Montserrat – about 100 miles to the north of Dominica – where they interbred with the African slaves. To this day Montserrat is known as “The Emerald Isle of the Caribbean” due to the Irish ancestry of so many of its people.

In the 1970s the RTE TV programme “Radharc” featured some of these “black Irish” who had Irish names and spoke with Irish accents. Irish was spoken in Montserrat up until 1900.

Was John Finn one of those Irish slaves? Was he Marian’s ancestor?

The problem with that scenario is that Dominica was not under British control in the 17th century. It was ceded to the British by the French in 1763 and the British only established a colony there in 1805. It is possible of course that John Finn migrated or escaped there from Montserrat or one of the other British controlled islands.

A more likely explanation in my view is that he arrived there when the colony was set up or shortly after. He may have been a soldier or an administrator. (Irish people were very much involved with the running of the British Empire in the 19th century. Queen Victoria referred to the Irish as “the backbone of the Empire.”) He was possibly given land and slaves and thus begat the union that resulted in the “Jno-Finn” line which has come down to the present day.

We will never know for sure but I think it is a feasible scenario. The 19th century tallies with the “great-great-great grandfather” story that Marian was told whereas the 17th was too far back.

Whatever the truth I think it is fascinating that a possible early member of my family tree – there aren’t too many Finns around – established a blood line that survives in the tropical village of Castle Bruce in the beautiful island of Dominica.

Castle Bruce, Dominica. Photo courtesy of Andrew Mawby

David O’Riordan is an artist based in Ladysbridge in East Cork. He is an accomplished iconographer who will shortly have an exhibition of his work at the Cork County Library, County Hall, Cork (27th March – 26th April) with two Greek iconographers, Nikolaos Griniexakis and Eftychia Ilia. A native of nearby Midleton, he is also the Roman Catholic Parish Priest of Ladysbridge and Ballymacoda in the Diocese of Cloyne.

Fr David O’Riordan

I became aware of his work while doing photography for the Ordination Service book of William Crean who became Bishop of Cloyne on 27th January. I was asked to photograph one of David’s icons– of Saint Colman – that is on the wall at Cloyne Church. I was so struck by the beauty and professionalism of the image that I texted David to say so. A few days afterwards he asked if I’d mind photographing some of his other icons at his home in Ladysbridge as they were required for the County Library exhibition.

The icon of Saint Colman as it appeared in the Ordination Book

As I expected, the icon of Saint Colman was no fluke. Here was a collection of beautiful icons in various sizes and done to the highest standards of the genre. Icons are religious images more commonly associated with the Eastern Orthodox tradition than Western Christianity. The word iconography itself is from the Greek words for “image” and “to write”. The convention is to say that an icon has been written as opposed to painted as the artist, in producing an icon, is writing a religious story in picture form.

To those of us more familiar with traditional Western art icons can appear strange. They lack the three dimensional quality so familiar in paintings since the Renaissance. This is deliberate. They are not meant to be naturalistic. Instead they are replete with rich religious symbolism that has changed little in over 1,000 years. Colours, for example, are used to signify The Radiance of Heaven (gold), The Divine Life (red), Human Life (blue) and The Uncreated Light of God (white).

So, for example, Jesus is often depicted wearing a red garment underneath a blue one to symbolise God become Man whereas the garment colours are usually reversed for the Virgin Mary (a human gifted by God). Neither do they comply with the compositional conventions of more traditional art where the subject is usually off-centre: in icons the subject occupies the very centre of the frame in order to underline the centrality of the sacred presence.

The faces look odd to us too. This is also to do with symbolism. Eyes tend to be larger than natural, for example, in order to symbolise the spiritual eye looking beyond the material world. Likewise, the mouth is usually depicted much smaller than natural as it is often the source of empty or harmful words.

David working on an icon

They are painted – written – using another ancient method: egg tempera – a permanent fast-drying paint made with coloured pigment mixed with (free-range) egg yolk and purified water. This was the standard method of painting up until the 15th century when oils became the norm. Again, the very medium used underlines the traditional nature of the craft. And “craft” is used advisedly as there is little or no room for self-expression in iconography. Adherence to the tradition is paramount and icons are rarely if ever signed whereas our modern understanding of art is primarily one of the artist expressing himself or herself.

Preparing the egg tempera colours

In contradistinction to the formality and asceticism of his iconography David’s other art is abstract and wildly colourful and executed through the voluptuous medium of oils. It is hard to believe that it is the work of the same person who produced the icons. Here we are very much in the modern era with influences as diverse as Georgia O’Keeffe and Salvador Dali being evident.

One could say that his iconography and his modern-influenced art represents the sacred and the secular except that a religious sensitivity can also be detected in his modern paintings. Not in any conventional sense, of course, but a mystical reverence for the underlying nature of things can be detected in his work. Which, of course, given the man’s religious vocation, is not at all surprising.

Obviously, David O’Riordan is no mere Sunday painter. Which prompts the question: why haven’t the general public been given greater opportunities to see his work? Apart from the forthcoming County Library event the only other exhibition he has held (of icons) was in Ballyvourney years ago when he was curate in Macroom (he has also served in Castlelyons, Cobh and Clondrohid.) Certainly, his non-icon work deserves to be seen as well and one hopes that he will consider an exhibition in due course.

I live within 20 minutes drive time of Ballycotton in East Cork and I go there regularly to walk along the cliffs. It’s an easy route, there is a path all the way, and for a bit of undemanding exercise and fresh air it’s hard to beat. I usually walk as far as the headland beyond Ballytrasna – about 2.75 kms – and back again and this takes about 75 minutes.

You can walk further as far as Ballyandreen – another 0.75 kms – and either return whence you came or via the road back to the village. The former is the better option – for the views – unless you are one of those walkers who prefers a circular route.

To get there drive all the way through Ballycotton village. As you near the port stay on the main road – it veers up to the right – and continue all the way to the end where there is a car park next to the beginning of the walk. There’s a sign there with illustrations of the bird life to be found in the area (click on any of the photos for full size) :

One of the several stiles on the walk. They are there to prevent livestock from straying on to the path.

Ballytrasna. The headland in the distance is my destination.

An old lifebuoy at Ballytrasna. A modern one has recently been erected next to it.

The view east from the headland with Ballycotton Island in the distance.

On the return journey.

As you near the end of the walk there is a path down to “Paradise”, the name given to a popular swimming area in summer. The steps down are narrow and precipitous and most of the hand rail has long since disappeared. Be very careful or, if you dislike heights, avoid.

A note on the photography: camera used was the Sony RX100, a little pocket marvel. All photos were shot in RAW and processed in Adobe Camera Raw and Photoshop CS6.

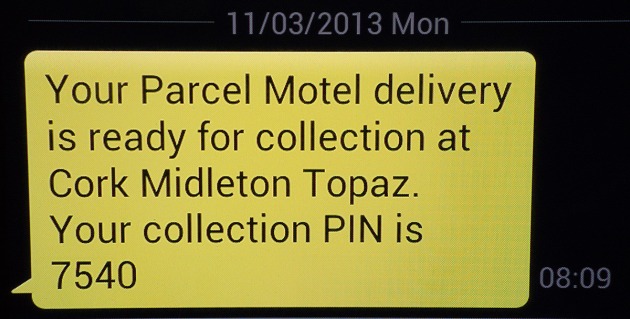

I’ve received my first delivery via Parcel Motel and the service has been excellent: easy, convenient and great value (in fact, it didn’t cost me anything in delivery charges as the first two are free.)

For full details see: http://www.parcelmotel.com

The item I ordered from Amazon.co.uk – a wine decanter- could not be shipped to the Republic of Ireland for some reason best known to Amazon. No problem. Parcel Motel provides its customers with two addresses – one in Dublin and the other in County Antrim. So, I chose the latter for my UK delivery. When it was received at the Parcel Motel address in Antrim it was couriered down to my local Parcel Motel at the Topaz Service Station in Midleton. They sent me a text and an email with the relevant PIN number and I picked it up within the hour.

The service is ideal for people who are at work when the post is delivered as it saves them the bother of having to go the local Post Office to collect the item. It is also ideal for purchasing items that Amazon and other retailers will not send to the Republic. Also, a lot of Amazon items are postage free within the UK (the item I ordered was) so you can save money even when paying the Parcel Motel delivery charge of €3.50.

This is the text I received to let me know that the item was ready for collection:

The Parcel Motel at Midleton:

You input your mobile number and PIN via a touchscreen and then the door opens and there’s the parcel:

The UK address on my parcel:

This is a brilliant service: quick and super-efficient. It is safe – all Parcel Motels are in 24-hour attended locations and are monitored by CCTV – and, for €3.50 per delivery, outstanding value.

Highly recommended.